Best perhaps to start with what it’s not. It’s not a form of futurology, or attempting to predict what has yet to take place. Few people during the tenure of Pope John Paul II would have predicted that his right-hand man would relinquish Peter’s throne in favour of an Argentinian Jesuit. Futurology is best left to those who make a living mugging companies by claiming to predict societal trends, and gamblers. It’s simply not academic.

Futurism, on the other hand, is an attempt to read the the present through how it depicts the future. This means looking at cultural outputs, such as art and literature which address future-related themes and analysing them.

Recently there has been a number of shifts in focus in this area, casting new light on how previously marginalised visions of the future, emerging primarily from non-caucasian communities, envisage the road ahead. Afrofuturism, or aesthetic depictions of the future from an African(-American) perspective(s), is the most prominent, but there have been many from a disparate range of sources, all now thankfully achieving academic scrutiny and consideration.

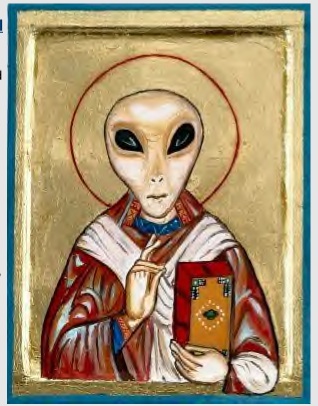

Religious faiths have not been excluded from this process, despite the predominance of atheist beliefs among those who produce Science Fiction and other futurisms. However, they have yet to attain similar levels of academic attention. I have an interest in how SF and cognate art modes consider the future of religion in general, and Catholicism and Buddhism in particular. Other scholars consider how the Hinduism, or Islam or other faiths are envisaged as developing (or dying) in the future.

Religious futurism can help us understand not only how art, but also how society is responding to evolutions in world theology in real-time. It can allow us to process better the role of religion in the world by understanding better how the world imagines religion will be in years to come.