Earlier this year, I started working on a project looking at manifestations of the Jewish state in alternative history literature. The seemingly intractable weeping wound that is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is, of course, a product of history, but a history which seems increasingly without any obvious resolution, or rather, one in which the much-vaunted two-state solution appears to satisfy almost no one.

After working on Science Fiction and Catholicism for some years, it seemed obvious to continue that work by examining Buddhist futurism. A book on this will, in the fullness of time, emerge, but for now readers will have to be satisfied with the sole tangible output to date, an article on Buddhist reception in Pulp Science Fiction. (Another on Arthur C. Clarke’s crypto-Buddhism, and one on the Zen influence over Frank Herbert’s Dune are also due to arrive in public shortly.)

But a second offshoot from that work on Catholic Futurism began to take shape in relation to Israel. Specifically, I wrote a chapter in that book on the cultural anxieties revealed by how Anglophone writers dealt with Catholicism through alternative history. The other timelines imagined by those writers were uniformally negative, envisaging retrograde Catholic empires crushing all science, innovation and progress under its clerical jackboot heel, which runs rather counter to the significant amount of support Catholicism has tended to offer to scientists historically.

Indeed, it says much more about how Anglophone writers, and specifically how ENGLAND perceives Catholicism – not as a cultural taproot but rather as a kind of fifth column infiltration which threatens their survival in an existentialist sense. This sentiment, I sometimes feel, is the archeological origin of things like opposition to the EU and the Brexit campaign.

Anyhow, when I began examining alternative history as a mode for exposing such cultural anxieties, it became quickly evident that the alternative timelines different cultures are drawn to evoke are a little like Rorschach blot tests, identifying their cultural anxieties in very clear ways.

As a test case, I chose Israel, primarily because it is in one sense a new nation, in another a very old one. Also, many writers of alternative history are culturally Jewish and this mode of artistic exploration is one that they are often drawn to. I was not disappointed by the results, and have been incorporating this work into my broader research project examining speculative geographies in literature.

Alternative histories about Israel reveal a series of cultural anxieties, from the obvious fear of Jewish annihilation (in early history at the hands of the Babylonians, Pharaonic Egypt or the Romans, but also during medieval pogroms in Europe, and obviously arising from the holocaust), as well as imagined reversals of such annihilation (particularly the fantasy of Judaic global dominance, sometimes by converting the Roman Empire).

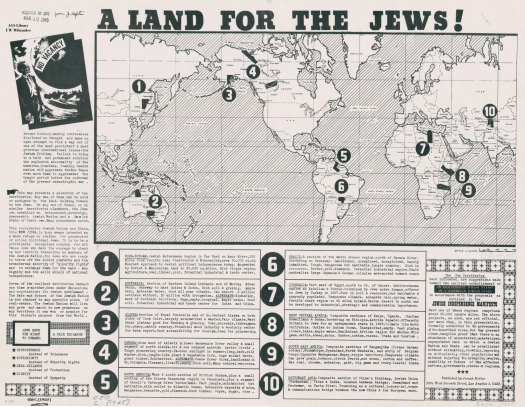

There is a particular phylum of these alternative histories which explores other geographic locations for a Jewish ethno-state. This is also real-world history, as the Zionist Council under Theodor Herzl did indeed consider locations other than historic Palestine for the creation of such a state. Actually many locations were seriously considered, by both Zionists and non-Zionists, and some territories were even offered by certain nations, during the interim between the emergence of Zionism as a political movement in the late 19th century and the creation of Israel in 1948.

I’ve been examining the literary manifestations of these real-world alternatives, to see in what way they unveil cultural anxiety about both the conflict with Palestinians and the Jewish relationship with Europe (from whence many current Israelis, especially the Ashkenazim, derive much of their cultural inheritance). This work has identified a strong sense of determinism about the current location of Israel which interestingly is secular and not predicated upon the religious diktat of the Old Testament (though of course the Promised Land of Eretz Israel remains a significant cultural driver within Israel itself, especially among the Orthodox community.)

I hope to publish something on this soon, when I get a moment. But for now, all I can offer you is a slide or two (above) from my latest conference presentation on the matter, which took place at the Specfic conference at Lund University in Sweden last week.