The jumping off point for this question is the seeming contradiction that the world is becoming more religious, not less, even as we are moving towards an ever more algorithm-led society.

It’s worth pointing out at the outset that this is less of a polarised binary than it may initially seem, of course, for a whole range of reasons. Firstly we can nibble at the roots of both immediate-to-medium-term predictions. What do we mean by ‘more religious’, exactly? Just because many more people in the next few decades will affiliate as Muslim or Catholic does not necessarily mean that the world will be more fundamentalist in its outlook (though that’s clearly possible.) They may simply affiliate as cultural positions, cherry-picking at dogmas and behaviours.

There’s not a lot of point in asking why about this, to my mind. Probably, issues like relative birth rates between religious communities and non-religious communities has a lot to do with things, I suspect. Geography, along with its varied sociocultural religious traditions, also play a significant role, as do the relative population decline (and geopolitical and cultural wane in influence) of the West, where atheism and agnosticism have been most notably prevalent since the fall of the formally atheistic Communist regimes in 1989/90.

We can similarly query the inevitability of the singularity, though there is absolutely no doubt that currently we are in an a spiral of increasing datafication of our world, as Douglas Rushkoff persuasively argues in his relatively recent neo-humanist book Team Human. And why is the world becoming so? As Rushkoff and others point out, it is in order to feed the development of Artificial Intelligence, which concomitantly makes us more machinic as a consequence. (This is again very well argued by Rushkoff.)

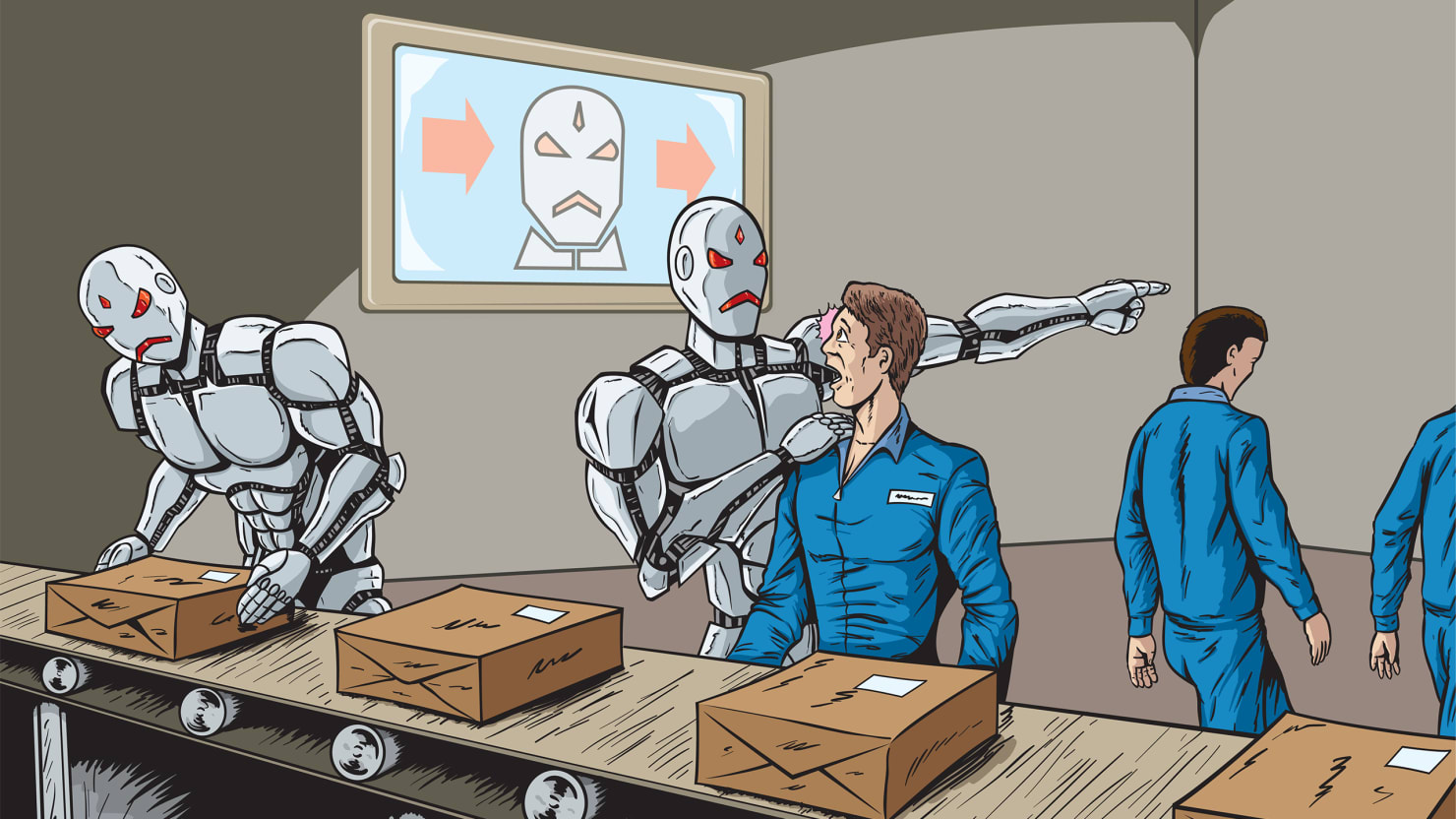

So, on the one hand we have a more religious population coming down the track, but on the other, that population will inhabit a world which requires them to be ever more machinic, ever more transhuman, conceived of as data generators and treated ever more machinically by the forces of hypercapitalism.

Let’s say that, as it looks today, both of these trends seem somewhat non-negotiable. Where does that leave us? A dystopian perspective (or a neo-Marxist one) might be that we will enter some kind of situation wherein a religion-doped global majority are easily manipulated and data-harvested by a coldly logical machinic hegemony (which the current global elite seem, with irrational confidence, to feel they will be able to guide to their own ends and enrichment.)

I feel that such a simple filtering into Eloi and Morlocks is unlikely. Primarily this is because I have (an irrational?) confidence that a degree of rationality is likely to intervene to mitigate the very worst excesses of this binary. Unlike Marx, I don’t consider those of religious faith to be drugged morons, for a start. Some (probably a large majority) of our finest thinkers throughout history into the present day have held religious beliefs which in no way prevented them from innovating in science, philosophy, engineering and cultural thought.

Similarly, I believe the current existence and popularity of leading thinkers expressing a firm affiliation with organic humanism (or to put it more accurately, a deeply suspicious antipathy to the alleged utopia of transhumanism) is a strong indication that a movement in defence of organic humanism is coming to the fore of our collective consciousness, perhaps just in time for us to consider the challenges of potentially imminent rule by the algorithms.

Thinkers like Rushkoff, or Yuval Noah Harari, have clearly expressed this concern, and I believe it is implicit in the work of many other futurists, like Nick Bostrom too. If it wasn’t, we would likely not have had the current explosion of interest in issues like AI ethics, which seek to explore how to mitigate the potential risks of machine disaffiliation from humankind, and ensure fairness to all humans who find more of their lives falling under algorithmic control.

But how might we explain this apparent dichotomy, and how might we mitigate it? Steven Pinker’s recent book Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters may offer some assistance.

Pinker summarises rationality as a post-Enlightenment intellectual toolkit featuring “Bayesian reasoning, that is evaluating beliefs in the face of evidence, distinguishing causation and correlation, logic, critical thinking, probability, game theory”, which seems as good a list as any I could think of, but argues that all of these are on the wane in our current society, leading to the rise of a wide range of irrationalities, such as “fake news, quack cures, conspiracy theorizing, post-truth rhetoric, [and] paranormal woo-woo.”

If, as Pinker argues, rationality is an efficient method mankind has developed in order to pursue our own (organic and human) goals, such as pleasure, emotion or human relationships, then we can conceive of it in terms divorced from ideology, as method rather than ethos. It’s possible, then, to conceive of, for example, people rationally pursuing ends which may be perceived as irrational, such as religious faith.

Pinker believes that most people function rationally in the spheres of their lives which they personally inhabit – the workplace, day-to-day life, and so on. The irrational, he argues, emerges in spheres we do not personally inhabit, such as the distant past or future, halls of power we cannot access, and metaphysical considerations.

Humans have happily and successfully been able to shift between these two modes for most (if not all) of their existence of course. As he rightly points out, there was no expectation to function solely rationally until well into the Enlightenment period. And indeed, we may add, in many cultural circumstances or locations, there still is no such expectation.

Why does irrationality emerge in these spheres we cannot access? Partly it is because the fact that we cannot directly access them opens up the possibility of non-rational analysis. But also, as Pinker notes, because we are disempowered in such spheres, it is uplifting psychologically to affiliate with uplifting or inspiring “good stories”.

We need not (as Pinker might) disregard this as a human weakness for magical thinking. Harari has pointed out that religion functions as one of the collective stories generated by humanity which facilitated mass collaboration and directly led to much of human civilisation.

But if we were to agree, with Rushkoff and contra the transhumanists and posthumanists, that the correct response to an ever more algorithmic existence is not to adapt ourselves to a machinic future, but instead to bend back our tools to our human control, then how might rationality assist that?

As a mode of logical praxis which is nevertheless embedded in and consistent with humanist ideals, rationality could function well as a bridge between organic human values and the encroachment of machinic and algorithmic logic. The problem, however, is how to interpolate rationality into those spheres which lie open to magical thinking.

It’s clear that the retreat into atomising silos of woo-woo, fake news, conspiracies and nonsense is not a useful or coherent response to the rise of the machines. Spheres like the halls of power must therefore be rendered MORE transparent, MORE accountable to the body of humanity, and cease to be the fiefdoms of billionaires, corporations and their political puppets.

However, obviously this is much harder to apply to issues of metaphysical concern. Even rationality only takes us so far when considering things like the nature of love or the meaning of life, those metaphysical concerns which, though ultimately inaccessible, nevertheless engage most of us from time to time.

But mankind developed religion as a response to this a long time ago, and has continued to utilise, hone and develop religious faith as a communal experience, bonding mechanism and mode of collaboration. And religion has stood the test of time in those regards. Not for all, and certainly not for those post-Enlightenment exclusive rationalists (ie agnostics and atheists, a population seemingly destined to play a smaller role in our immediate future, according to current prognoses.)

If the positive ramifications of religion can be fostered, in a context of mutual respect, then it seems to me that there is no inherent contradiction or polarisation necessary. Indeed, a kind of Aquinian détente is perfectly possible. Rationality may be our best defence against an algorithmic hegemony, but rationality itself must acknowledge its own limitations of remit.

As long as the advocates of exclusive rationalism continue to view religious adherents (without distinction as to the form of their faiths or the presence or absence of fundamentalism) as their primary enemy and concern, they are in fact fighting the wars of a previous century, even while the bigger threat is posed by the hyperlogical opponent.

We therefore have a third option on the table, beyond the binary of gleeful acquiescence to algorithmic slavery (transhumanism) or a technophobic and Luddite-like retreat into woo-woo (which is equally no defence to machinic hegemony.) An accommodating rationality, operating as it always did in the spheres we do inhabit, has the potential to navigate this tricky Scylla and Charybdis.

To paraphrase someone who was not without rationality, we could usefully render unto rationality that which is open to rationality, and render unto God (of whatever flavour) that which is for now only open to God.

But we do need to open up some spheres to rationality which currently are not open to most of humanity – the power structures, the wealth imbalances, the blind gallop into faith in the algorithm. Because, pace the posthumanist faith in a benign singularity, there’s no guarantee that machinic merger or domination will preserve us, and even if it does, it will not conserve us as we know ourselves today.

A very useful piece of work.