I carry Neanderthal DNA in my body. I am one of the modern humans, homo sapiens sapiens, who are descended from hybrid cross-hominid fertilisation that likely occurred somewhen during the overlap of populations in paelolithic Europe.

Of course, that side of the family died out a long time ago, leaving my sapiens ancestors to colonise Europe and indeed everywhere else on the planet.

I often wonder what we lost when we lost our hominid relatives – the Neanderthals, the Denisovans, the hobbit-like Homo Floriensis and so on. What might a world of multiple hominid species be like? How might we have accommodated our stronger, carnivorous and less gracile Neanderthal population? What might our tiny cousin with grapefruit-sized heads, the Floriensis hobbits, have contributed to our world?

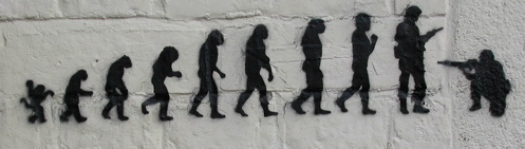

Anyhow, the more I ponder the roads not taken, the less impressed I have become with our own boastful claims and achievements. Not simply because human achievement increasingly has come at the expense of all other species (initially the large mammals, then our fellow hominids, and now basically everything else). But also because even those achievements, it seems to me, may not really be ours to claim.

Air flight, modern medicine, computers? For sure. We made those. But let’s go back upstream to the origins of civilisation to see whose civilisation is it really?

Neanderthals used fire. Indeed, probably homo erectus, the ur-granddaddy of hominids used fire. Fire is a major issue. No other animal uses it. Most run terrified from it. But hominids tamed it, and found ways to use it for cooking and heat. If there’s one development which most explains why hairless apes like us and not, say, the gorillas or big cats rule this world, it is probably the taming of fire.

Neanderthals also buried their dead. This is a sobering thought really. In some senses so do elephants, and other species also demonstrate evidence of mourning, loss and grief. We may feel that grief is one of the things which makes us human, but it’s not an exclusively human sentiment. Even taking it to the point of ritual behaviour – burial – is not exclusive to us.

But what of the other foundational components of human culture and society? What about clothing, art, science, religion?

Well, Neanderthals made jewellery from seashells and animal teeth. Neanderthals created artwork on cave walls. Neanderthals invented musical instruments, specifically bone flutes. We can presume they knew how to beat on drums or rocks rhythmically too. After all, they also had hand axes, which would have been made and used with such rhythmical hitting. Neanderthals built stone shrines, and where there are shrines, it is highly likely that ritualistic behaviour took place.

Neanderthals used lissoirs, and hence invented hide preparation, and hence clothing. They invented glue and string and throwing spears which they used to hunt large game. These hunts required collective action and collaboration. Recent evidence suggests that Neanderthals may even have learnt to count and actually recorded their counting by notching scratches on bones.

So perhaps this isn’t OUR civilisation at all, when you think about it. Perhaps we are thieves living in someone else’s house, whom we murdered, looking at their achievements and claiming them as our own.